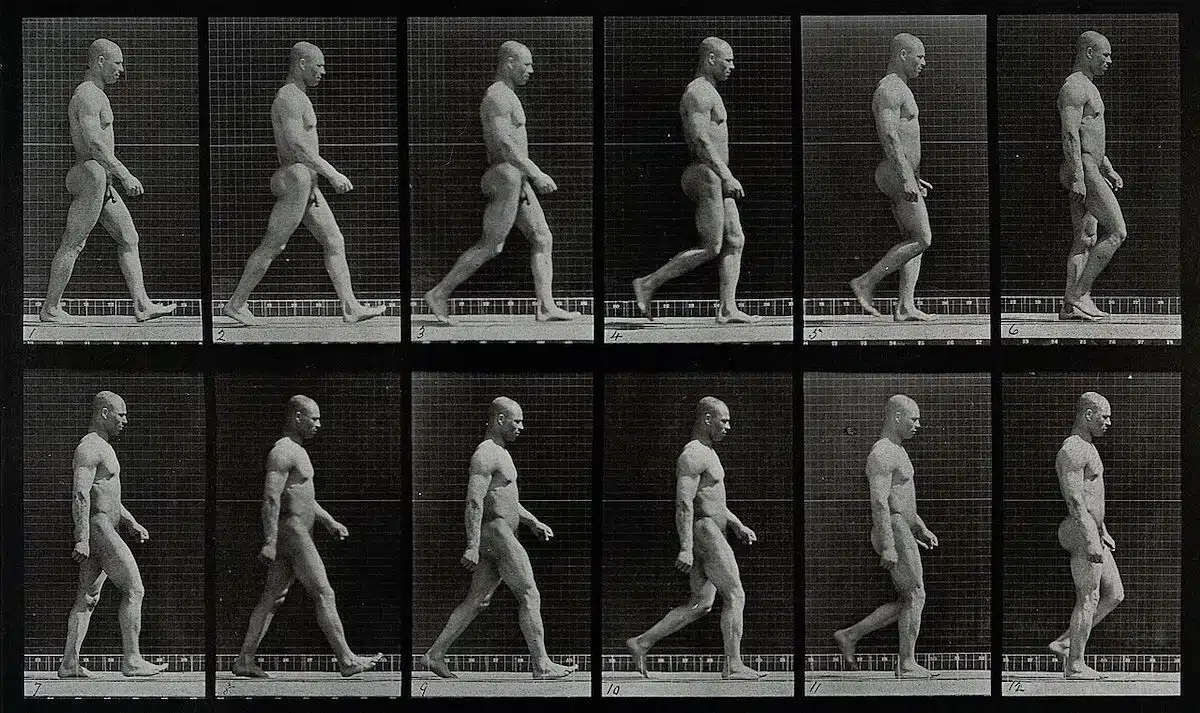

Animating a walk cycle is one of the most basic tasks in animation because walking is such an essential movement for humans. However, it is surprisingly tricky to craft. Why? Because walking is a highly complicated series of coordinated movements involving the rotation of many different joints.

Fear not! The human walk has been broken down into a series of poses and codified by many of our finest animation educators: people like Thomas & Johnston, Richard Williams, Whitaker & Halas, and others have laid the framework. All we need to do is follow their recipe, work methodically and patiently, and success is all but assured.

If you would like to follow the tutorial on video, here it is. However, this blog post can also fit the bill. Let’s get started!

Work on After Effects or Whatever You Like

If you would like to work on the same file I worked on, you can download it from here. However, you don’t need to do this exercise on After Effects if you don’t want to. If you would prefer to work traditionally on a program like Toon Boom, or on a 3d program like Maya, Blender or C4D, you certainly can. The poses will be the same, and you will even be able to add some details that 2d puppet animators won’t be able to provide, like rotation of the shoulders and waist. (More on that later.)

If you do work on a 3d program, please turn off inverse kinematics. For many kinds of movement, it is helpful; for the walk cycle, it just tends to get in the way.

In this tutorial, we will be working on a walk cycle on the 12s, meaning each step takes 12 frames (on a 24 frames per second timeline) so that the cycle repeats every second. This is a common pace for human walking, but of course, people walk at different speeds. A faster walk might be on the 8s; a slower walk might be on the 16s.

Our Rig

The After Effects work file is set up with no source files. The parts of the body are created with solids shaped by mattes. The rig is set up so that expression controls on a null object named WALKING MAN RIG manage the angle of each part of the body, and the torso is parented to that null object. All you will need to animate is the expression controls and the position keyframe of that null object.

If you would prefer to work on a 3D rig, here are some that are free to download:

Heel-to-Toe, Right Leg Forward (Frames 1 and 25)

The heel-to-toe position is the first pose when making a walk cycle, and in many ways it is the most important. If you see a walk cycle that looks wrong, chances are the heel-to-toe is where the problems start.

The only contact with the ground is light: the back toe is touching and the edge of the front heel is touching. The front leg is completely straight; the back leg is only very slightly bent. The arms go in opposite directions to the legs on their side. That is, when the right leg goes forward, the left arm goes back; when the left leg is back, the right arm is forward. I like to put a little bend on the front elbow then straighten it out when it goes back, so that it doesn’t look too stiff.

Once you have created this pose on frame 1 copy all the keyframes and paste them onto frame 25. Set the work area to end at frame 24; this way the walk cycle will loop over a second.

Common mistakes that beginning animators make with this pose are bending the knees too much and having too much contact with the ground.

Heel-to-Toe, Left Leg Forward (Frame 13)

This is the same pose as the right leg forward, but we reverse the position of the legs and arms so that what was forward is back, and what was back now goes forward.

One quick note on how we are working, since it is a pattern that you will repeat many times when you work on digital character animation. We are setting the basic timing by placing the key poses first; that is, the poses with furthest reach of movement. Then we go back to the middle of that stretch and define the pose there, and then we split these halves into quarters, quarters into eighths, etc. This allows us to shape the flows and arcs of a movement just the way we want, while keeping a steady pace.

I like to set the keyframes for all the controls that are likely to be animated just because it drives me crazy when I go back to a pose and see that it has been changed by a tweak I made further ahead. Other people work in different ways! You will eventually find your preferred method.

Passing (Frames 7 and 19)

In the first passing pose, the left leg is passing a planted right leg. The right leg is straight; the left leg is bent with the knee forward and the sole angled to the ground. The arms have swung down so they are both by the sides. If you set the extremes of the arms at the three heel-to-toes, you shouldn’t need to touch the arms; the keyframe interpolation will do the work for you.

Once you have set the passing pose in frame 7, skip to frame 19 and create the same pose, but with the legs reversed: that is, the left leg planted and the right leg passing.

A common mistake with this pose is having the passing foot too high in the air; it is actually just clearing the ground.

Landing (Frames 4 and 16)

Right after the heel-to-toe, when the body is nearly flying through the air with the barest contact to the ground, comes the landing pose. In frame 4, this is when the right foot lands full on the ground, the right knee bends to absorb the impact, and the left foot rises off the ground. This is the pose where the body is lowest.

The most common mistake here is not angling the foot sufficiently. The sole should be facing backwards, very nearly perpendicular to the ground. This is counter-intuitive, but it is the way humans usually walk.

After you have set the right foot landing in frame 4, skip to frame 16 and reverse the pose, so that the left foot is landing.

Push-off (Frames 10 and 22)

After the passing pose in frame 7, in frame 10 the body pushes off to begin a new step. The left knee rises and the right foot elevates on the toe. At this point, the body is at the highest point of the walk.

Advance to frame 22 and reverse the legs and arms.

Common mistakes on this pose are having the foot flat on the floor or raising the foot too much off the floor (as I did, before fixing, in the video tutorial!)

If you have gotten this far, congratulations! You have finished your walk cycle. Press preview and take a good look at your animation. Are there any hitches in your walk cycle? If there are, go through each pose and see where the kink is and try to work it out.

If you are drawing your walk cycle traditionally, or if you are working on 3D, you have the opportunity to add a detail that 2D puppet-style animators can’t add (at least not with fancier rigging): that is, the turn of the shoulders and hips.

Torso Movements

In the walk cycle, the torso counter-turns in the opposite way. That is, when the left arm is swinging forward, the left shoulder turns forward, and the left hip turns back in the opposite direction. Then when the left arm swings back the spiral motion turns the other way: the left shoulder turns back and the left hip turns forward. The right side mirrors these positions.

Before we move on to compositing, remember that there are some subtle variations between how animators do the walk cycle. Here I write about how Richard Williams’ walk cycle is different from Preston Blair’s.

Compositing

Many of these walk cycle tutorials don’t include the important step of compositing. I have created a simple scene (also just with solids) so you can have the experience of compositing your walk cycle onto a background.

Open the scene entitled SCENE FOR COMPOSITING and drag the comp you have been working on into the scene. You will need to shrink the comp so that it is relative in scale to the background.

Now turn on time remapping for that layer and create keyframes at frame 1 and 24. Copy those two frames and paste them at frame 25 (or 1:01, in time code). You now have the walk cycle looping twice, over two seconds. You can repeat this process as much as you like.

Next, create a null object and place it right underneath the heel of the front foot. If you move one frame forward, you will find that the foot is no longer aligned with the null object. Simply move the comp forward so that the heel is over the null object again. This assures that the character doesn’t slide over the ground as he is walking.

Now move forward in your comp one frame, and repeat. This frame-to-frame adjustment is necessary when compositing a walk because the forward movement of the character is irregular.

In this exercise, we are compositing a comp over another comp, but in many workflows you will need to adjust the position of the character right in the scene. The same principles apply; adjust the movement of your rig on a frame-by-frame basis.

You have now created a walk cycle and composited it in a scene. But your investigations are just beginning! Here are some suggestions for further study.

The Sneak

The Sneak is when a character is trying to walk without making much noise. That means he/she needs to put their feet down gently. To dramatize that, the up-and-down movement is exaggerated. This is a good example of how animators poeticize a movement. Here is good documentation of a female sneak. And here is the inimitable Richard Williams on the sneak, giving some credit to Warner Brothers’ Ken Harris.

The Marilyn Monroe Walk

Marilyn Monroe is a bit of a caricature of femininity, which makes her a good reference for animation, which as a rule adores exaggeration.

This video from YouTube makes the essential features of the hyper-feminine walk even more clear:

Since the hips of a woman are wider than a man’s, women need to angle their legs inward a bit in order to get their feet under their center of gravity. (Models on a catwalk exaggerate this by actually crossing the centerline.) As a result of this, the hips have to rotate just not on the y axis, but on the x axis as well.

Also, notice that the arms are very loose and away from the body. This creates more of a counter-balance to compensate for the wider hips.

Keep on Investigating!

Although it can be challenging, the walk cycle is a great entry into more advanced character animation. In this tutorial, we’ve worked on what we might call the ‘Vanilla’ Walk Cycle – a very general description of how humans, male or female, walk. But character animation is about character! It is about finding specificity.

When you’re out on the street, train your eye to look at how people walk. If someone has a very idiosyncratic walk, try to define for yourself what makes it so. As with drawing, good animation begins with seeing – actual, intentional seeing.

Another helpful tip: try things out in your body. For instance, when you are walking, try exaggerating the rotation of your shoulders and hips on the y axis. Pretty soon, you will find yourself not just walking but swaggering. You instantly feel more powerful and confident.

Or try walking like Marilyn Monroe! It’s delightful to feel another character in your body, and that experience can feed your ability to design movements. As a way of signing off, let me introduce myself. I used to teach animation at the New York Film Academy, but about 11 years ago I started an animation studio called IdeaRocket. Apart from 2d and 3d, we work in whiteboard, mixed media, and motion graphics. We make explainer videos for marketing or internal purposes. Animation has provided a great career for me and I love it more than when I first started!