Animation and comics have a lot of crossover. Animated video and graphic novels are both driven by compelling characters, meticulous narrative pacing, and grueling serialized production schedules, yet both leave room for artists, designers, create incredible, creative work. The rise of digital production, new media, and changing roles for artists and animators is still transforming the way that we create and consume animation and comics. To get a handle on the current state of both fields—and the crossover between the two—we talked with comic book artist, illustrator, writer, and animator, Mike Cavallaro.

Mike Cavallaro is originally from New Jersey, where he attended the Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic Art. He has worked in the comics and animation industries since the early ‘90s. Mike’s clients include Archie Comics, BOOM! Studios, DC Comics, First Second Books, IDW Publishing, Image Comics, Marvel Comics, MTV Animation, Valiant Comics, Cartoon Network, Warner Brothers Animation, and others. Mike shares his thoughts on animated video production, the current state of comics, and the skills you need as an animator, artist, and creator to crossover from animation to comics, or vice versa. Enjoy.

Animation and Comics: The Crossover

Shawn Forno: You’ve worked in both industries—animation and comics. What similarities do you see between comics and other graphic novels and animation? What are some of the biggest differences?

Mike Cavallaro: In the U.S., the major divide is between the direct market and the book market.

If your experience working in comics is within the direct market, there are many similarities to the animation industry:

- They both lean heavily towards serialized, episodic storytelling

- They both tend to be work-for-hire situations (the artists who created the work don’t own it)

- They’re both deadline-oriented, with an “assembly line” approach and a division of labor that divides the workload among numerous highly-skilled specialists to produce the script, pencils/storyboards, inks, colors, lettering, etc. In comics, there’s an editor overseeing this workflow, in animation there’s a producer.

The book market arose as an alternative to this when traditional publishers like Pantheon, Macmillan, and others became interested in comics as a medium rather than a genre. This occurred mostly in the wake of critical and financial successes like Art Spiegelman’s MAUS and Alan Moore’s WATCHMEN. Now almost every major publisher has a graphic novel imprint.

A cartoonist publishing their work in the book market is treated more like an author than a technician. There are fewer similarities to be found between this and the animation industry:

- Authors tend to own their work and have a great deal of leeway to negotiate foreign and multi-media rights

- Book market graphic novels have schedules, yes, but they’re much less grueling than those in the direct market and animation. Alison Bechdel took seven years to complete FUN HOME. David Mazzuchelli took over ten years to complete ASTERIOS POLYP. These sorts if deadlines are unheard of in the direct market

- Book market graphic novels tend to be the work of a sole auteur, rather than an assembly line production

- Graphic novels are typically over 144 pages, which even within series such as Kazu Kabuishi’s AMULET or Jeff Smith’s BONE, provides for a more satisfying chunk of story than the typical 22-page comic, or 11-minute or 24-minute episode.

So lots of similarities between the direct market and animation, where the corporation owns the creations and the work itself, and the process is more industrialized and less personal. Fewer similarities between the book market and animation, where the former stresses individual ownership and profit sharing, and a more personal voice in the final product. I’ve segued between all of them but my preference is to create my own projects and publish them via book market publishers.

Animation and Comics: The Production Process

Shawn Forno: What’s the most underrated production step in the comic process?

Mike Cavallaro: It has to be the lettering. Back in the day, lettering was done during the thumb nailing/layout stage because cartooning greats like Milton Caniff understood that the word balloons were part of the composition and were as important as any other graphic element on the page in directing the reader’s eye through the layout. But with the advent of digital production, lettering on a Marvel or DC Comic, for example, tends to happen last.

Word balloons sometimes have to be forced into artwork that never took them into consideration. Editors will actually trim down the script when things don’t fit. It can lead to a very haphazard reading experience.

Shawn Forno: What’s the most underrated production step in animation?

Mike Cavallaro: You know, that’s really hard to answer! I have to say, in my experience on numerous animated series, nothing jumps out at me as having received the short end of the stick. What I’ve seen is great care and diligence at every stage of the process. Each builds on the previous stage and it all has to work in concert or the whole thing collapses. Problem areas frequently include overseas in-betweening, where nuanced gestures and acting can be lost in translation, but that’s not because in-betweening is “underrated”, it’s just a pitfall in the process.

Shawn Forno: So what’s the biggest difference in the production process between animation and comics, then? Is it storyboarding, edits, revisions—something else?

Mike Cavallaro: In general, the comics production process is a lot freer and more forgiving than animation. Much of the animation process is fixed and very technical. Comics are a much older tradition, and even with the advent of the digital work environment, if you can make a mark you can probably print it.

Editorially, it gets into those markets again, which is another reason I went into that in such great detail. In animation or a direct market comic book, the artist is a “pair of hands” or a “hired gun.” On the other hand, if you’re the author and owner of your graphic novel project, revisions are more likely to take the form of a request and a conversation rather than an order.

Animation and Comics: The Digital Future

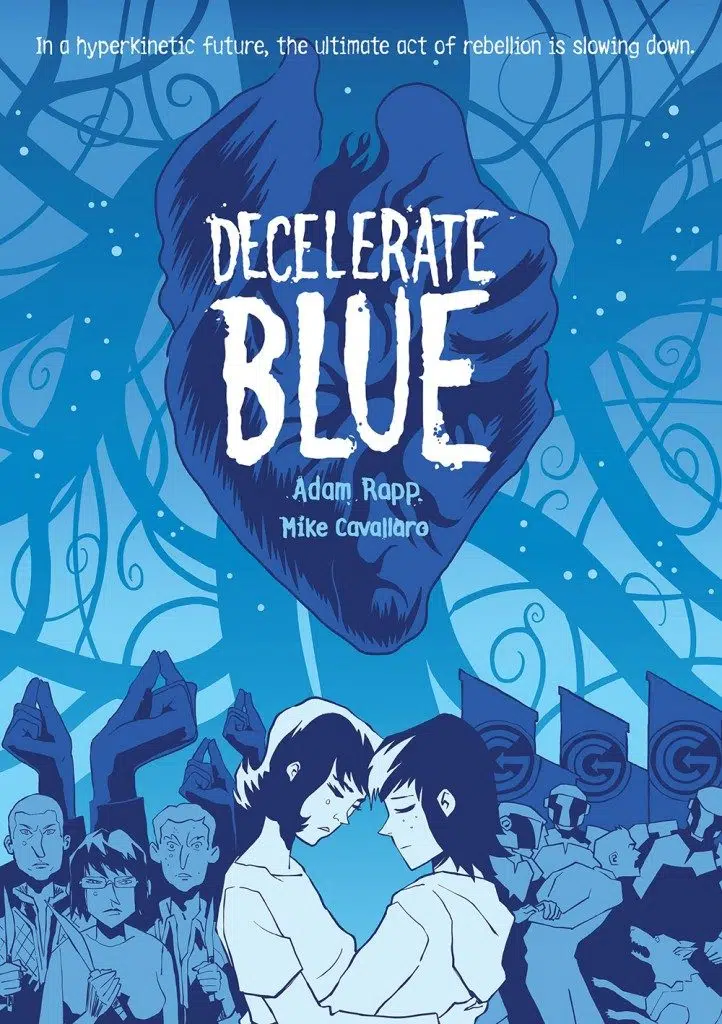

Shawn Forno: Your latest book — DECELERATE BLUE — addresses the ultra-fast pace of consumerism life in the near future. How do you think animation and comics have changed with the speed of digital media?

Mike Cavallaro: If you go back to masterpieces like Milton Caniff’s TERRY and the PIRATES, the story unfolded in daily, 4-or-5-panel installments over twelve years! It’s a completely different mindset than anyone would tolerate in this age of binge-watching entire seasons over a weekend.Format should relate to whatever best delivers your content. When I worked on Cartoon Network’s CODENAME: KIDS NEXT DOOR, we had the same 11-minute format as ADVENTURE TIME, so that’s nothing new. Personally, I love the format for comedy or adventure-comedy shows. It’s not so great for straight-up adventure because you need more time to develop and resolve those types of stories.

My current project began as self-contained, 4-page comics in an anthology magazine, but I like telling layered stories with tangled storylines. I like large casts of characters accidentally tripping each other up and working at cross odds for comedic effect. I always cite Woody Allen stories. It was very hard to pull that off in four pages. Impossible, actually. So now it’s a 186-page graphic novel. I’ve expanded the format instead of shortening it. But that’s what the story demanded.

Shawn Forno: What advice do you have for illustrators or colorists looking to make the jump from comics to animation or vice versa?

Mike Cavallaro: One of the upsides of animation is that it’s an extremely professional, well-structured industry. We’re mostly freelancers but we go to work from 10 – 7, get weekends off, frequently receive benefits, and know when a project will begin and end. If you’re an animator thinking about segueing into comics, most of that will go out the window. Build a nest egg before jumping ship or prepare to go hungry. All the comic book artists I’ve known who’ve gone the other way—to animation—have had an easier time for the same reasons. Animation is just so much more reasonable than comics in regards to deadlines and workload. Animation also pays better and pays more consistently.

The page rate for comic book coloring has actually gone down over the last 20 years. The internet and digital coloring lets you instantly send pages anywhere in the world—including places where the cost of living is low. An average rate nowadays is $65 per page, and a colorist might do two of those per day. Meanwhile, coloring backgrounds for animation is the exact same process but pays more than twice as much on salary rather than by the piece. On the other hand, if you can get a piece of the royalties while coloring a popular comic book, it could be quite profitable. So there are a number of factors to consider.

I’d tell both parties to cultivate a foothold in both industries. I don’t see any reason to choose between the two. For people who enjoy sequential narrative art, my advice would be to find a balance between comics and animation. Animation provides the income, stability, and benefits comics lack. Comics provide the possibility for creative expression not typically found in the animation industry.

Shawn Forno: Do you ever see your comics through the lens of an animator? How does your animation background inform your current work?

Mike Cavallaro: From a purely creative standpoint I think comics are a more subtle, more versatile storytelling medium than animation. What I think I got from animation is a shorthand approach to drawing and coloring. A lot of comics seem to revel in obsessive detail, and I don’t really see the point of that.

I also pay a lot of attention to comedic timing and dialogue in film and animation. Onscreen characterizations are stronger and more consistent characterizations than I’ve previously found in comics. I get a lot more inspiration from the dialogue in various Cartoon Network shows, or even in things like episodes of 30 Rock or Parks and Recreation, than any of the writing in the comics I grew up reading, though that’s starting to change for a lot of the reasons I’ve mentioned.

Find out more about Mike Cavallaro’s work at mikecavallaro.com. You can check out his latest book, Decelerate Blue, a collaboration with playwright Adam Rapp. Ask for it at your local bookstore or order it straight from the publisher.